您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

India is increasingly positioning electronic waste as a strategic lever in its critical mineral policy, seeking to reduce near-total import dependence on materials vital to electric mobility, defence systems and advanced technologies. With global supply chains unsettled and China maintaining dominance across several critical mineral segments, New Delhi is accelerating efforts to recover lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements from domestic e-waste streams. Policymakers view “urban mining” as a short-term buffer while domestic mining projects, which may take a decade to mature, remain under development.

{alcircleadd}Explore- Most accurate data to drive business decisions with Global ALuminium Industry Outlook 2026 across the value chain

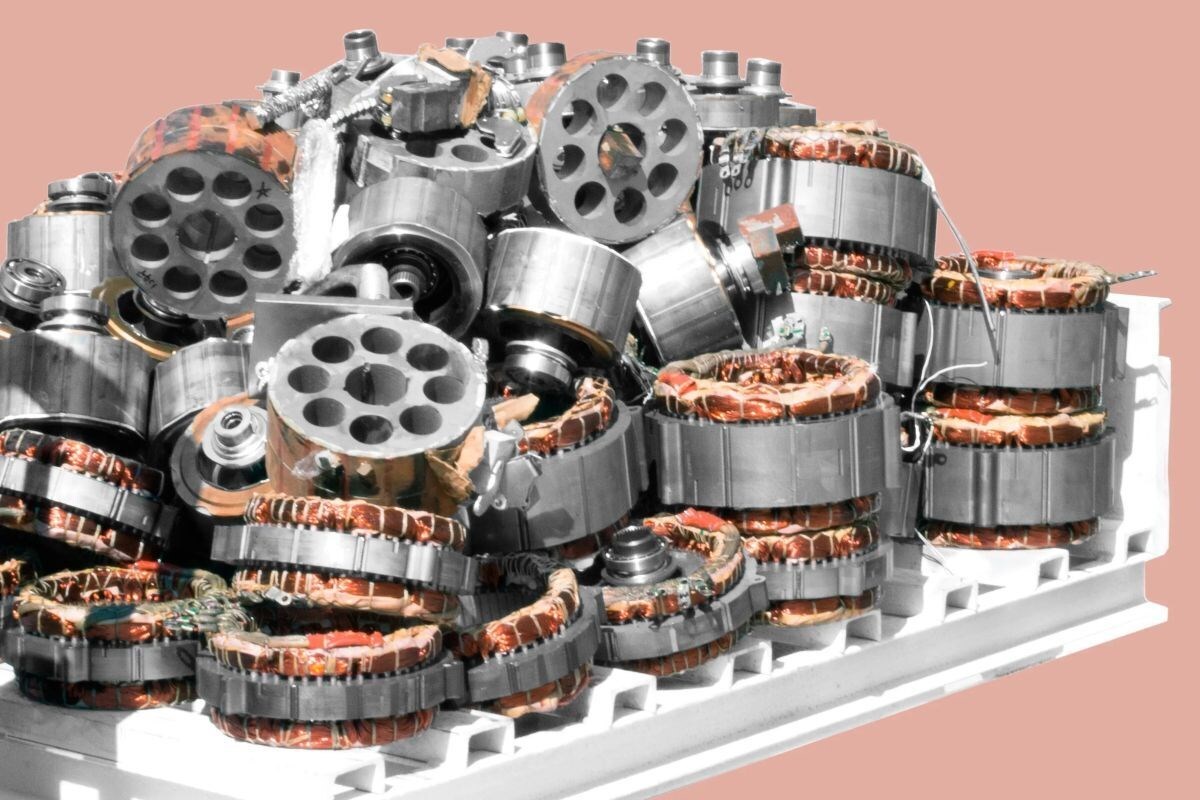

In 2025, India generated almost 1.5 million tonnes of e-waste, though experts suggest the actual figure may be significantly higher. Within this growing waste stream lies a valuable secondary resource base, discarded batteries containing lithium, cobalt and nickel, circuit boards containing platinum and palladium, as well as hard drives holding rare earth magnets.

At Exigo Recycling’s facility in Haryana, end-of-life lithium-ion batteries are processed into black mass, refined chemically and converted into lithium powder. Examining the final product, the facility's lead scientist termed it “White gold”.

Policy-push and efforts at formalisation

According to industry estimates, urban mining could generate up to USD 6 billion annually, offering partial insulation from global supply disruptions.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis reported India’s current “100 per cent import dependency” for key critical minerals, including lithium, cobalt and nickel.

To back domestic recovery capacity, the government approved a USD 170 million programme in 2025, aimed at expanding formal recycling infrastructure for critical minerals. The initiative is founded on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulations that mandate manufacturers to channel e-waste through authorised recyclers.

Raman Singh, Managing Director at Exigo Recycling, stated, “EPR has acted as a primary catalyst in terms of bringing scale to the recycling industry.”

Explaining that structural changes are underway, Attero Recycling’s Nitin Gupta said, “Before EPR was fully implemented, 99 per cent of e-waste was being recycled in the informal sector. About 60 per cent has now moved to formal.”

However, a substantial portion of India’s e-waste continues to flow through informal dismantling networks. While these channels are critical for collection, they typically recover high-value scrap metals such as copper and aluminium, leaving many critical minerals unrecovered.

Informal sector – backbone but bottleneck?

“India's informal sector remains the backbone of waste collection and sorting,” said Sandip Chatterjee, Senior Adviser at Sustainable Electronics Recycling International, warning that informal processing leads to “loss of critical minerals”.

Environmental and occupational hazards associated with informal recycling, such as open burning, acid leaching and unsafe dismantling, also undermine sustainability objectives. In Delhi’s Seelampuri recycling hub, informal traders continue to handle large volumes of scrap.

Integration to reduce critical mineral loss

Recognising this gap, stakeholders are exploring integration strategies to bring informal actors into traceable supply chains. “Integrating informal actors into traceable supply chains could substantially reduce” the mineral losses at early stages, Chatterjee added.

Ecowork, India’s only authorised non-profit e-waste recycler, is working to formalise skills and improve recovery efficiency through structured training.

Regarding training methods, Operations Manager Devesh Tiwari mentioned, “Our training covers dismantling and the (full) process for informal workers.” “We tell them about the hazards, the valuable critical minerals, and how they can do it the right way so the material's value doesn't drop.”

Rizwan Saifi, at its facility, extracted a permanent magnet from a discarded hard drive for rare earth recovery. “Earlier, all we would care about was copper and aluminium because that is what was high-value in the scrap market,” he said, and added, “But now we know how valuable this magnet is.”

As India advances its broader critical mineral strategy, urban mining is emerging not merely as a waste management solution but as a policy instrument, supporting supply chain resilience, reducing import shocks, and strengthening domestic capabilities in strategic materials.

Image source: https://www.alcircle.com/

Don't miss out- Buyers are looking for your products on our B2B platform

Responses