您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

Imagine running a factory where one input dominates the cost structure and suddenly, far richer buyers start paying more for the same supply. That is the pressure aluminium smelters are now facing which affacets the overall aluminium smelting outlook 2026. From Europe to Australia to the United States, competition for electricity is quietly deciding which plants keep operating, which manage partial restarts, and which slip into permanent shutdown.

{alcircleadd}The output is retreating across several regions. The explanation is not found in metal markets, but in megawatts.

When electricity becomes the real raw material

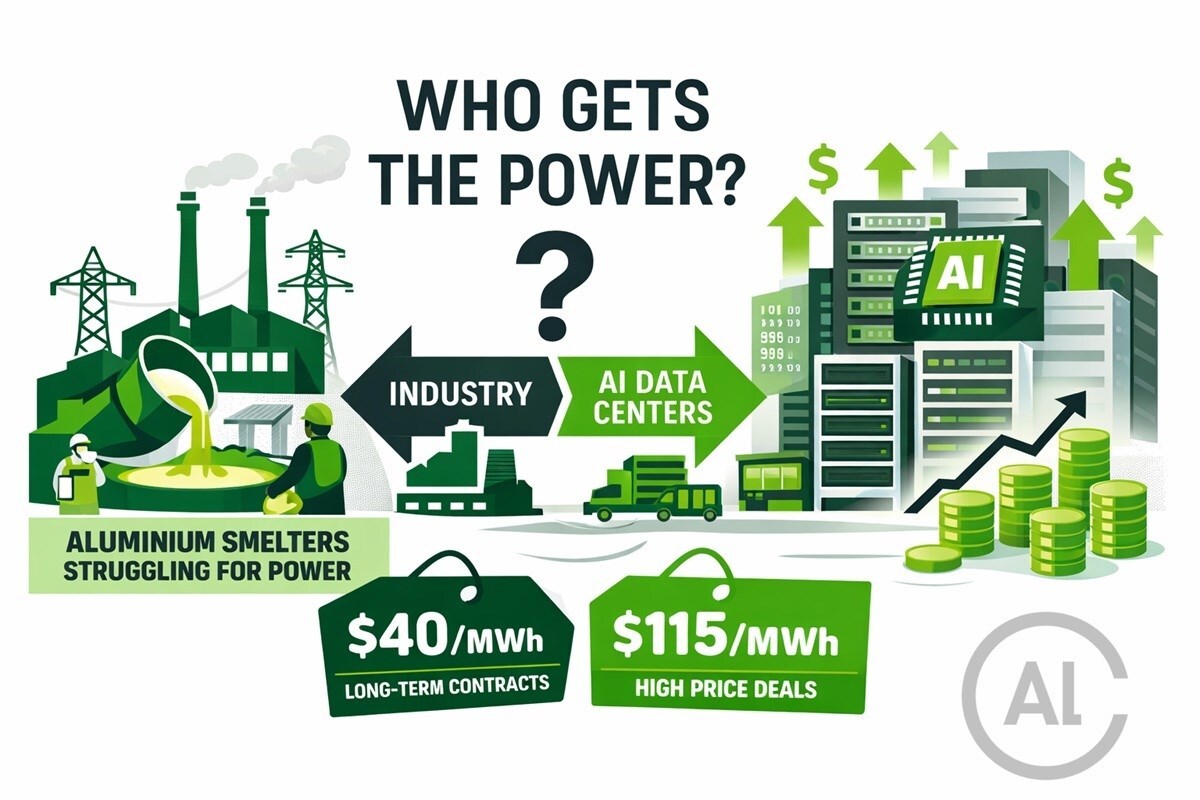

What does it take to make aluminium competitive for global aluminium outlook 2026? Not ore, not labour - but power. Electricity accounts for roughly 30-50 per cent of smelting costs, and the economics only work with long-term contracts spanning 10-20 years at around USD 40/MWh. That model is now under siege.

Who is outbidding smelters? AI data centres. Tech companies are locking in electricity at prices above USD 115/MWh, reshaping power markets and leaving energy-intensive industries struggling to compete. Outside China, this has become the single biggest obstacle regarding the smelters.

The result? Smelters are not shutting because aluminium prices are weak - they are shutting because electricity has become scarce, volatile, and unaffordable.

Australia: can one power contract decide a country’s output?

Tomago Aluminium, Australia’s largest smelter, located near Newcastle, NSW, produces up to 590,000 tonnes per year, employs more than 1,500 people, and consumes around 10 per cent of NSW’s electricity. Energy already accounts for over 40 per cent of its costs. It is facing potential closure beyond 2028 due to high energy costs and difficulty securing renewable power.

What will happen in 2028? That question now dominates industry and policy discussions. Talks are ongoing with the Australian government, including possible support measures, but no certainty exists yet.

The national implications are stark. Australia produced 1.57 million tonnes of aluminium in 2024 and an estimated 1.63 million tonnes in 2025. Output is expected to stay near 1.64 million tonnes through 2028. But if Tomago get in 2028, production would fall sharply to around 1.066 million tonnes. If it remains operational, output would hold steady. To get the accurate data read: Global Aluminium Industry Outlook 2026.

Mozambique and Europe: how much uncertainty can a smelter absorb?

In Mozambique, the pressure is already translating into losses. South32 has cut investment in its Mozal smelter, suspending pot relining work and threatening to put the whole operation on care and maintenance if it doesn’t reach a new power agreement by March 2026. The expected loss in FY25: USD 372 million.

The capacity of Mozal is 560,000 tonnes. In 2025, it has produced approximately 355,000 tonnes. However, without the resolution of the power uncertainty, it is expected to decline to 240,000 tonnes in 2026. The negotiations are in progress with the Government of Mozambique, Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa, and Eskom, but as yet, there has been no progress to instill confidence in the availability of a reliable electricity supply. Even as the Q3 FY25 production increased by 3 per cent to 93,000 tonnes, the trend is still downwards.

European story is more extensive – and structural. Since 2008, primary aluminium capacity has declined by 40 per cent with the reduction from 4.8 million tonnes of annual capacity to 2.9 million tonnes by 2025. Volatility in energy prices, particularly since 2022, has hastened the shut-downs, roughly 800,000 tonnes of capacity is idle aftermath of 2022 energy crisis.

Which smelters are already gone? Speira’s Rheinwerk plant in Germany has permanently shut its 120,000-tonne primary operation and shifted fully to recycling. Aldel’s Farmsum smelter in the Netherlands has been suspended since 2021 with no restart plans. In Iceland, Nordural’s Grundartangi smelter has idled about two-thirds of its 320,000-tonne capacity after a potline failure in October 2025, with a full restart uncertain even by mid-2026.

Others are barely holding on. TRIMET’s Essen smelter runs at roughly 50 per cent capacity, while its Hamburg and Voerde plants continue with around 30 per cent output cuts. Slovalco in Slovakia remains fully idled, Talum in Slovenia has been offline since 2023, and Alcoa’s San Ciprián smelter in Spain has not produced since December 2021.

But apart from this many smelters are in operation and is producing to meet the demand of the country. To Know more details read: Global Aluminium Industry Outlook 2026.

United States: can protection offset power competition?

The US aluminium outlook 2026 industry offers a long-term view of what sustained power pressure looks like. Since 1998, the number of operating smelters has fallen by about 75 per cent, from more than 20 to just five by late 2025. Capacity has dropped from roughly 4.5 million tonnes to about 2.4 million tonnes.

Today, only four primary smelters remain active, producing around 700,000 - 900,000 tonnes per year. Power competition with data centres remains intense, and 2025 tariff hikes to 50 per cent on aluminium imports have provided limited breathing room.

Century Aluminium’s Mount Holly smelter in South Carolina is operating at about 75 per cent capacity and investing USD50 million to restart more than 50,000 tonnes of idled lines, targeting full output by June 2026 under a power extension through 2031 with Santee Cooper.

Hawesville in Kentucky remains curtailed due to energy costs, while Sebree continues steady operations. Alcoa’s Warrick facility in Indiana sustains partial output, and Massena West in New York relies on hydro power but faces growing grid pressure. Magnitude 7 Metals exited the primary market entirely in January 2024.

New proposals are starting to surface, such as Century’s plan for a DOE-funded greenfield aluminium smelter with potential capacity of up to 1 million tonnes. However, with site selection not expected until late 2026, any new production remains several years away.

In the end, it all comes down to one thing: who can actually secure affordable, reliable power to keep these smelters running, a question explored in more detail in Global Aluminium Industry Outlook 2026.

Don’t miss out- Buyers are looking for your products on our B2B platform

Responses