您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

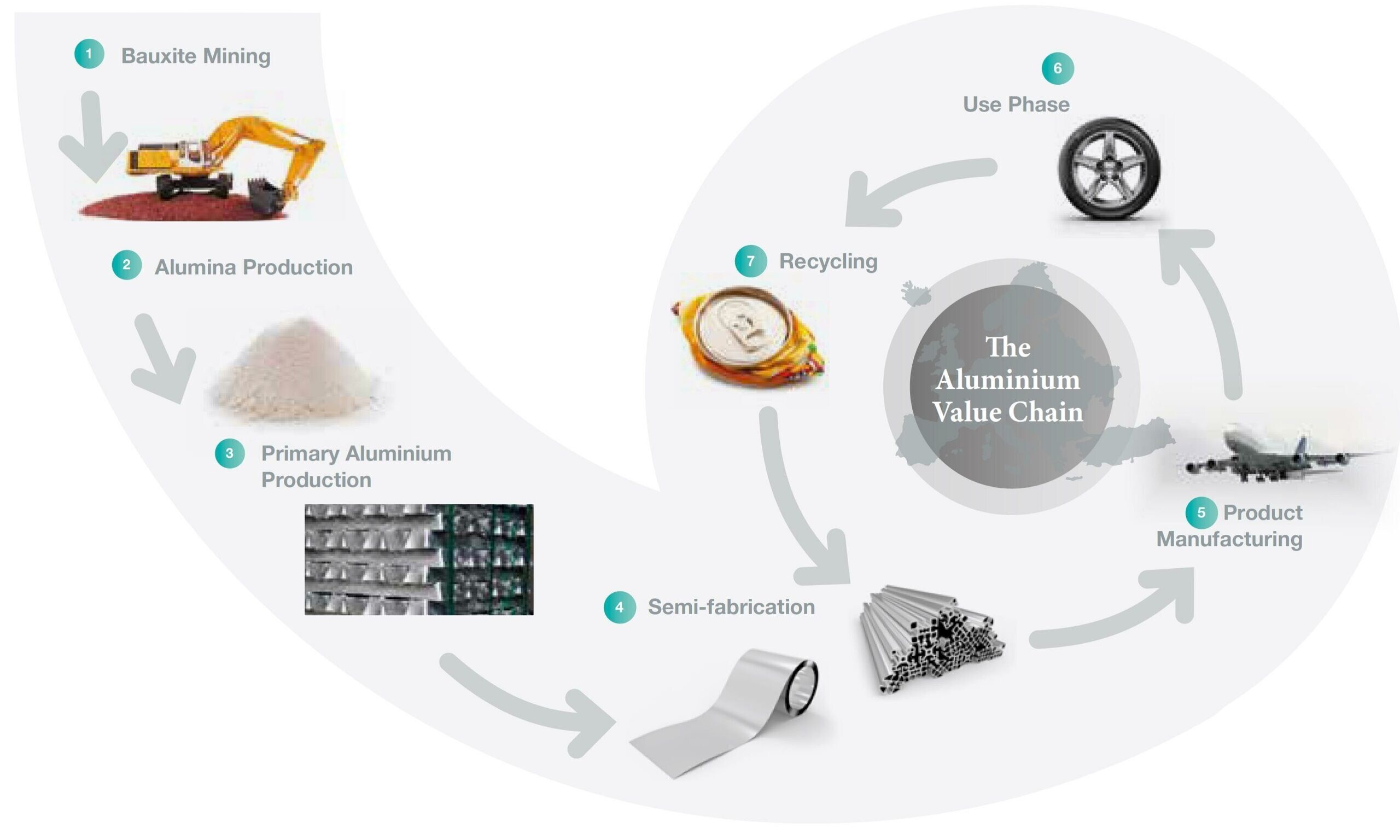

The aluminium industry sits at a stark juncture where demand tied to the energy transition is set to surge. But is it a viable choice, bearing the short-term and long-term impact? Industry projections point to roughly an 80 per cent rise in aluminium demand by 2050, while the sector itself remains an outsized emitter, with direct emissions concentrated in primary production and global sector emissions measured in the order of gigatonnes. Meeting downstream demand for “green” metal while slashing the sector’s own footprint is not optional: it is an existential commercial imperative. The choice facing producers is binary in economic terms. Invest now, absorb large up-front costs and capture a durable price and capital advantage; or delay, preserve short-term margins and face growing regulatory, market and financing penalties that will erode competitiveness.

Image source: https://www.basystems.co.uk/

Image source: https://www.basystems.co.uk/

Also read: Fastmarkets proposes CBAM cost integration into aluminium P1020A premiums

Dual role of aluminium in the energy transition

The capital arithmetic is unforgiving and unambiguous. Retrofitting existing primary smelters with inert-anode technology is recognised as a pathway widely recognised as the only credible route to eliminate direct process emissions at scale, and carries an estimated cumulative price tag of roughly USD 200 billion to 2050. That equates to about USD 7 billion a year, roughly a 38 per cent uplift over the sector’s ordinary annual capital expenditure. The industry’s current structural profile — typical profit margins near 13 per cent and a sector WACC around 9 per cent- means internal cashflow alone cannot shoulder this burden.

At the same time, credible price signals for low-carbon metal exist. Market participants reported green premium bids approaching USD 50 per tonne in 2024 for aluminium certified to strict sub-4 tonnes of CO2e per tonne smelter intensity thresholds. That premium is the mechanism through which investors hope to recoup the large inert-anode and renewables capex — but the premium alone is insufficient unless it is underpinned by standardised certification, long-term offtakes and predictable policy.

Decarbonisation has two levers of very different scales. Electrifying production with low-carbon power wherin replacing captive fossil generation with renewables and firming solutions becomes the imperative and represents the largest single opportunity, with potential savings on the order of hundreds of millions of tonnes of CO2e by mid-century if deployed rapidly.

Yet aluminium smelting requires reliable baseload power; integrating variable renewables implies additional system costs for storage, hydrogen, demand response and grid upgrades. Those complementary investments are non-trivial and must be planned alongside plant retrofits.

…and so much more!

SIGN UP / LOGINResponses