您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

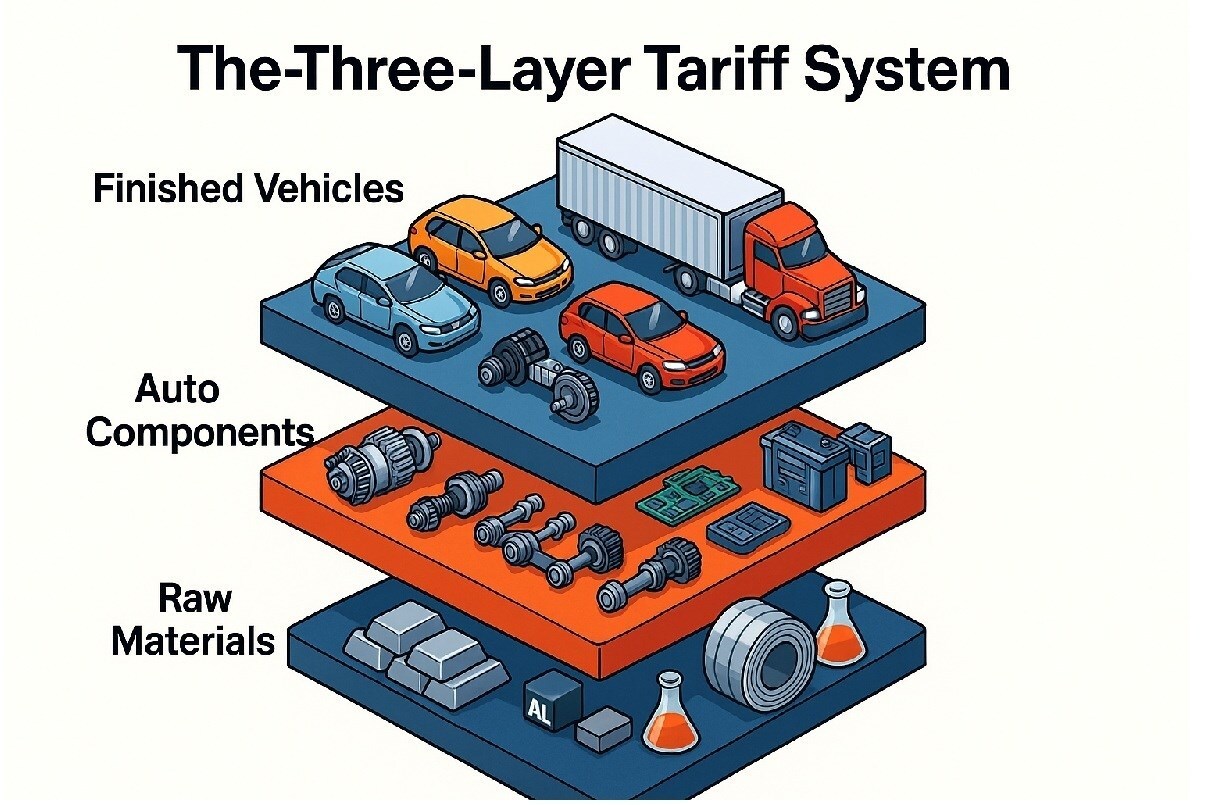

As tariffs rolled out this year, the automotive sector found itself navigating a policy shift that swiftly reconfigured supply chains, trade patterns and production decisions across markets. The tariff campaign on the automotive sector began with the first round of 25 per cent duties on April 3, hitting imported passenger cars, SUVs and light trucks under 14,000 pounds, instantly raising their costs and giving domestic producers such as GM and Ford a fresh competitive advantage. A second wave followed on May 3, this time directed at engines, transmissions, drivelines and electrical systems including batteries and wiring harnesses.

Although manufacturers were granted a brief window to front-load inventories, the pressure was immediate, especially for those unable to meet USMCA’s 75 per cent North American content threshold.

The framework hardened again on October 17 when Washington extended 25 per cent duties to medium- and heavy-duty vehicles and their parts, while buses were pulled in at a 10 per cent rate. These measures took effect on November 1 and sat on top of existing steel and aluminium tariffs that were already raising costs across commercial fleets.

By imposing tariffs on both complete vehicles and the parts used to assemble them, the US ended up shielding its automakers from overseas rivals even as it pushed their manufacturing costs higher — a contradiction that reshaped the industry.

…and so much more!

SIGN UP / LOGINResponses