您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

There’s a neat paradox at the heart of the clean-energy debate: richer societies typically use more energy, yet the latest modelling from the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) suggests we can (provided that we choose to) have a lot more of the good things that energy delivers (travel, cooling, manufacturing) while using less energy overall. The ETC’s October 2025 briefing argues that smart electrification, appliance efficiency and material recycling could let the global economy more than double by 2050 while cutting final energy demand by about 24 per cent compared with today.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/

Also read: High time to invest in Africa’s solar potential! Why? It records the highest ‘sunshine’ on Earth

That claim is startling because it rewrites a default storyline: growth equals more energy, which in turn leads to more emissions. The ETC’s subtler point focuses on energy productivity, the economic output we squeeze from each unit of energy, and shows how technology and systems change can deliver magnified services (kilometres travelled, heated and cooled floors, industrial output) with far smaller energy inputs.

In the ETC’s central scenario, kilometres travelled by car rise about 70 per cent and air travel by 150 per cent by 2050, while cooled floor area expands by roughly 150 per cent. Yet final energy for those services falls because electric technologies and better design are far more efficient.

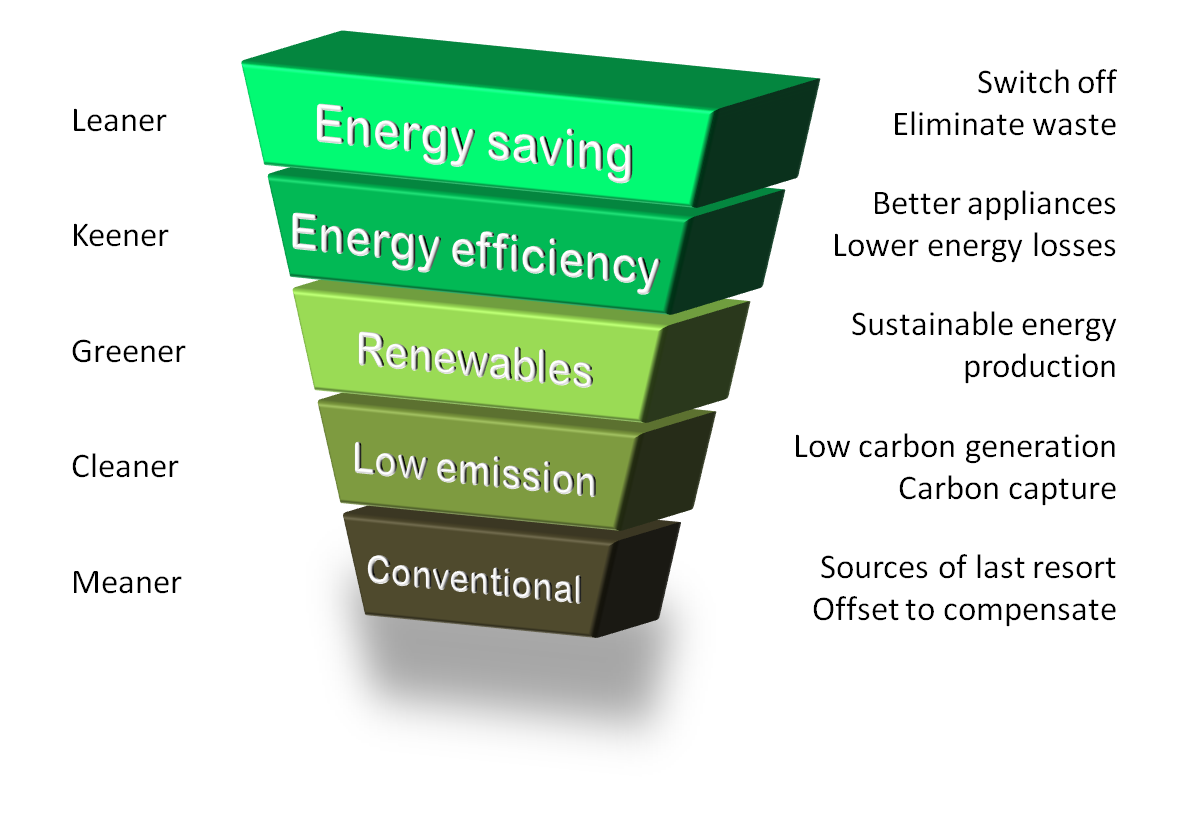

Why this works

Electrification is inherently more efficient. Battery electric vehicles convert a much higher share of input energy into motion than internal combustion engines. Heat pumps produce three to four times the heat per unit of electricity compared with gas boilers, and electric cooking is several times more efficient than traditional biomass or open-flame methods. The ETC uses these real-world efficiency gaps to show how switching fuels and devices transforms the energy maths.

Instead of hand-waving, ETC offers momentous figures that capture the scale of the opportunity like the energy-productivity measures that could reduce final energy (the energy that appliances, vehicles and buildings actually use) by around 24 per cent by 2050 relative to today, and primary energy (the raw fuels needed) by roughly 36 per cent, even while delivering a materially larger set of services and a doubling of GDP.

…and so much more!

SIGN UP / LOGINResponses