您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

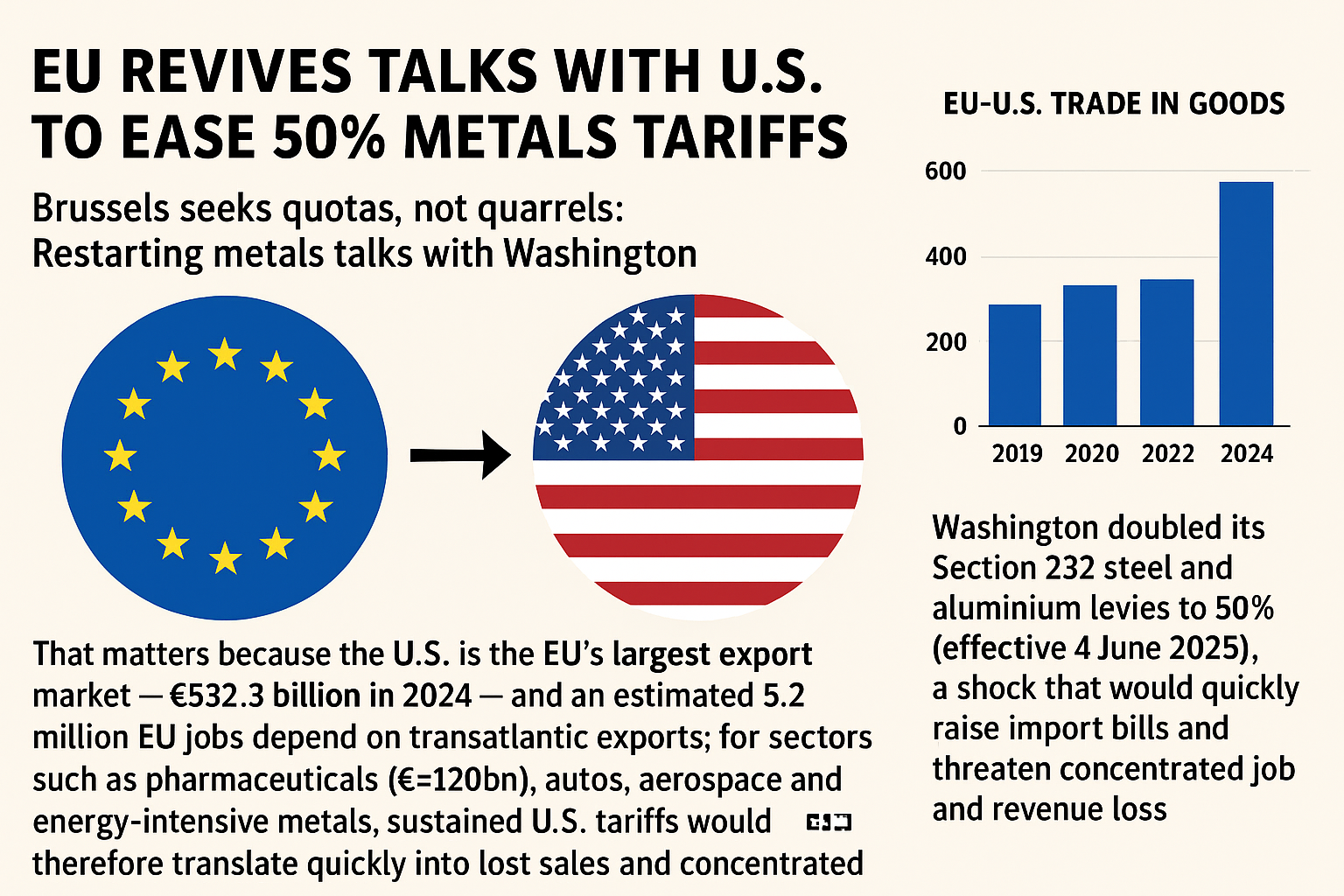

On Wednesday, the European Union announced its intention to resume discussions with the United States regarding the reduction of Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium. This move comes as various nations seek to address ongoing trade tensions. EU Trade Commissioner Maros Sefcovic is scheduled to meet with US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer in the coming days to discuss the possibility of removing or reducing the current tariffs, as Sefcovic informed a Bloomberg reporter. But does European Union really need to stress on negotiation when they are accustomed with the ‘tariff structure’ from long before?

Image for representational purposes only

Image for representational purposes only

The European Union has had its own tariff policy

While the United States has taken the centre stage for the past 8years or so whenever the word ‘tariff’ has been uttered, it is evidently not the only one implementing tariffs on others. The European Union has long been involved in the ball game of tariffs.

1) Treaty of Rome and the birth of a common external tariff (1957 to 1968): The Treaty of Rome (1957) created the EEC’s Common Commercial Policy and set the legal basis for a customs union. Over the 1950s–60s, the six countries that came together for the treaty, i.e. Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, removed internal customs duties and introduced a single Common External Tariff that the Community applied to trade with non-members — i.e., the EU collectively set tariffs on imports from other countries

2) Agricultural protection under the CAP (1960s onward): Agriculture was treated as a special sector from the start wherein the Common Agricultural Policy introduced substantial market-support measures (price supports, intervention buying and external protection) that effectively meant high external tariffs and tariff-rate quotas on many agricultural goods for decades, though CAP reforms since the 1990s have reduced price support and changed how protection is delivered.

3) Trade defence duties (anti-dumping, countervailing and safeguards): As international trade grew, the EU developed and routinely uses trade-defence instruments — anti-dumping and anti-subsidy (countervailing) duties and safeguard measures — to impose duties on imports judged to be dumped, subsidised or causing injury to EU industry. These are applied case-by-case after investigations by the European Commission and are a central tool for imposing tariffs targeted at specific products/countries. The Commission has also reformed and modernised these instruments in recent years.

4) Tariff reductions via trade agreements (preferential elimination, not new tariffs).

From the 1990s onward, the EU has also used free-trade and association agreements to remove tariffs bilaterally or regionally (for example, CETA with Canada, provisionally applied from 21 Sept 2017, and the EU–Japan EPA from February 2019, each eliminating duties on the vast majority of tariff lines). These agreements show the flip side of EU tariff policy: actively cutting tariffs as part of negotiated deals.

5) Retaliatory / counter-tariffs and political responses (examples: 2018 & 2025 episodes): The EU has also imposed retaliatory tariffs in response to third-country measures (i.e., tariffs imposed on the EU). A prominent example: after the US Section 232 steel and aluminium tariffs in 2018, the EU announced countermeasures (lists of US goods subject to duties) and implemented duties covering several billion euros of US exports; some of those measures were later suspended pending talks, and the EU has signalled it will react again when necessary. More recent episodes (2024–25) show the EU preparing or re-applying countermeasures when faced with renewed extra-EU tariffs.

…and so much more!

SIGN UP / LOGINResponses