您想继续阅读英文文章还

是切换到中文?

是切换到中文?

THINK ALUMINIUM THINK AL CIRCLE

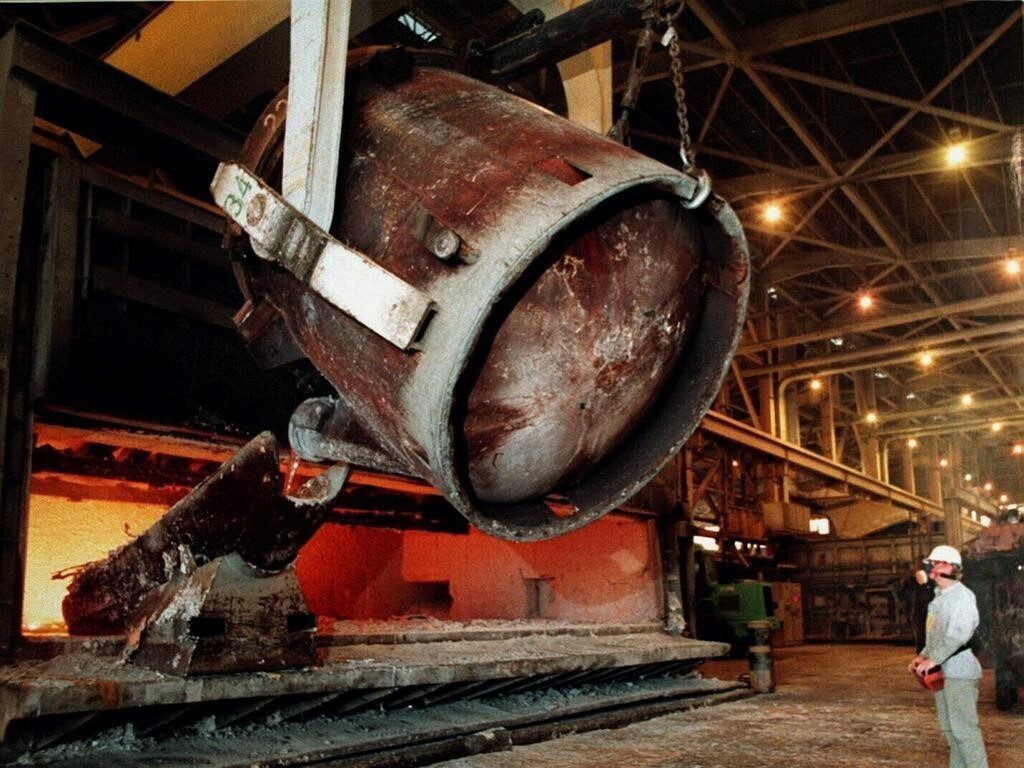

Amid a string of challenges like a projected USD 90 million loss in Q2, delays in the recommencement of the Kwinana refinery, and production setbacks at the San Ciprián aluminium smelter in Spain due to a power outage that has unsettled Alcoa itself as well as the global aluminium industry, the reassuring message about the Portland aluminium smelter in Victoria has brought a sense of relief. Chief Executive Officer William Oplinger has ruled out all the plans to shut down the facility for at least the next decade, announcing stark contrasting news to the troubled San Ciprián smelter, which faces disruptions even before resuming the full operations as planned. He expressed, "I am sick of closing sites. I am much more focused on the Portland side, of trying to make sure we can get it repowered because I think Portland is a great plant with a great workforce and a good technology."

Doubtful about energy storage, yet confident in operations – how?

However, amid an optimistic outlook on the Portland smelter, Oplinger has doubts about battery storage as a viable firming power solution for the smelter's growing dependence on variable renewable energy sources like wind and solar. This stance differs from Rio Tinto's approach, which sees batteries as a promising solution to support its Boyne smelter in Queensland, citing rapidly declining energy storage costs. The differing perspectives between Rio Tinto and Alcoa can be better understood by examining the broader context of each company's approach to renewable energy usage.

Alcoa's Portland aluminium smelter in Victoria and Rio Tinto's Queensland smelter are among the largest aluminium smelters in Australia, each consuming a substantial share of their respective state's electricity. While Rio Tinto has made considerable progress in its energy transition, with 80 per cent of its Boyne smelter's power now sourced from renewables, Alcoa's Portland smelter currently draws 40 per cent of its energy from renewable sources, including a nearby wind farm. The company has also signed memorandums of understanding with the Kentbruck Green Power Hub and Alinta Energy to support the proposed Spinifex offshore wind project. Additionally, a nine-year agreement with AGL Energy, signed last year, will provide 287 megawatts of renewable energy to the smelter starting mid-2026.

Aluminium smelters in Australia started shifting towards renewable power, aligned with the country's energy transition. Renewables now account for nearly 40 per cent of the national electricity supply, driven by strong investment in large-scale projects and rooftop solar. In 2024, the country added a record 7.5 gigawatts of new renewable capacity.

Against this backdrop, Rio Tinto's aluminium head, Jérôme Pécresse, initiated a study into battery storage for the Boyne smelter as part of an effort to expand the use of firm renewables. However, Alcoa CEO William Oplinger remains sceptical, expressing doubt that battery storage can economically or practically serve as a reliable renewable energy source for large-scale smelting operations.

"I have not seen an economic business case that says batteries can be built big enough to back up a smelter," he told the Melbourne Mining Club on Thursday, May 1.

He added, "Wind and solar, firmed with other energy sources, is the way to go for many countries, specifically Australia. You've got ample solar, you've got ample wind resources, [the challenge] is going to be firming it with something. One of the things that Australia needs to figure out is: what is that back-up source? I am not convinced it is batteries yet."

…and so much more!

SIGN UP / LOGINResponses